Every Patch Agent has its Own Story (1) - Martian: Exploring the Unknown with Sophisticated Tools

- Haein Lee, Insu Yun

- Atlantis patch

- October 15, 2025

Table of Contents

As we mentioned in our previous blog post, we enhanced the patching capabilities of Atlantis by ensembling multiple patch agents. In this series of blog posts, we will introduce each of our patch agents in detail and explain the rationale behind their designs.

Diversity for Good

To maximize the effectiveness of ensembling, it is crucial to have diverse agents. If all agents are similar, the ensemble will not perform significantly better than any individual agent. Therefore, we intentionally designed our patch agents to be diverse in their approaches, methodologies, and also models used. We newly developed six patch agents, each with its own unique architecture and motivation, as summarized in the table below.

+---------------+----------------+----------------------------------------------+------------------------------+

| Agent | Architecture | Motivation | Used Models |

+---------------+----------------+----------------------------------------------+------------------------------+

| Martian | Workflow | Simple workflow yet complex tools | o4-mini, claude-4-sonnet |

| MultiRetrieval| Agent | Iterative retrieval and patching | claude-3.7-sonnet, o4-mini |

| Prism | Multi-agent | Multi-agent system for long-context handling | o4-mini |

| Vincent | Workflow | Property-based approach for guided patching | gemini-2.5-pro |

| Claudelike | Agent | Patch generation inspired by Claude code | claude-3.7-sonnet |

| Eraser | Workflow | Use of custom model for specialized tasks | Custom model |

+---------------+----------------+----------------------------------------------+------------------------------+

Martian: Into the Unknown, Armed with Sophisticated Tools

We first introduce Martian, a patch agent that employs a straightforward workflow but leverages sophisticated tools. The name “Martian” reflects its approach of exploring the unknown, much like a Martian would, by utilizing advanced tools to navigate and understand unfamiliar terrain.

Dawn on Mars: The Birth of Martian Agent

In the beginning, our focus was on prompt engineering — how to craft the right prompts to give open-source AI agents like Aider and SWE-agent the best possible guidance.

Our earliest approach was quite simple: providing crash logs such as an ASAN report directly to the agents.

Over time, we explored more advanced strategies, such as parsing stack traces and supplying related source code snippets alongside them.

We called each individual piece of information an insight, and we experimented with various combinations of these insights to improve the agent’s understanding.

(In our codebase, you can find these insight generators in insighter/services.)

However, by late 2024 and early 2025, as LLM models rapidly evolved, it became clear that prompt engineering alone was no longer enough.

We now had to consider tool usage, conversational flow, long-term memory, and structured outputs.

In this transition from prompt engineering to context engineering, we decided to build our own agent to experiment with flexible architectures and richer contextual reasoning — and thus, Martian Agent was born.

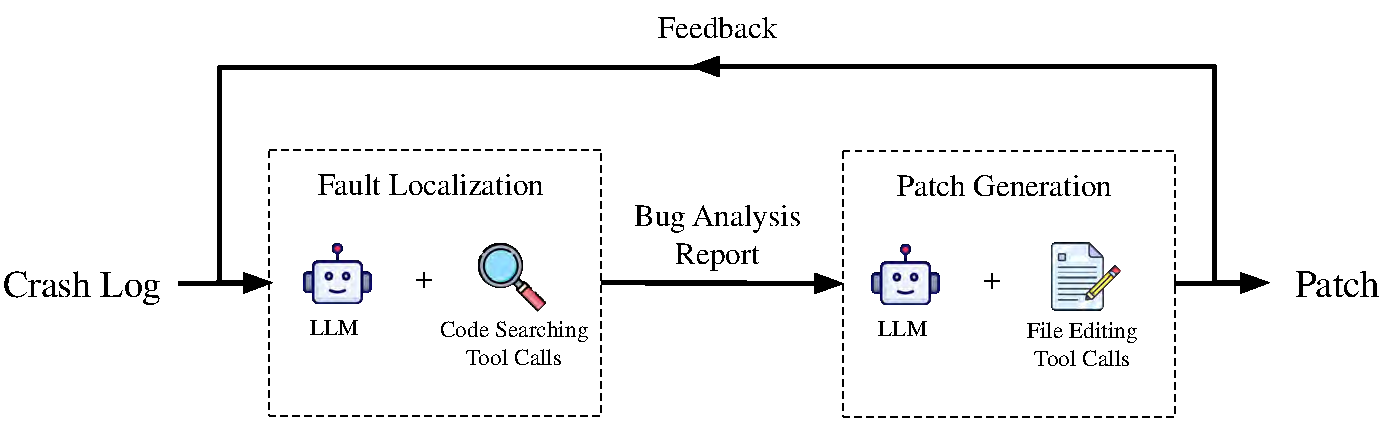

Martian Agent was built upon two key design principles. First, we separated fault localization and patch generation to optimize context management. Since the LLM’s context window is limited, providing precisely the right information at each stage is crucial. fault localization and patch generation each pose significant but distinct challenges, so we found it more effective to handle them independently, each with its own tailored context. Second, we need an environment that allows us to easily test and integrate different tools. To achieve this, we developed a ReAct-based agent framework on top of LangChain, flexibly incorporating various tools. This helps us to rapidly prototype and tune the agent’s capabilities through the competition testing.

Inside the Martian Agent

The overall structure of Martian Agent is as follows:

Fig.1 High-level overview of Martian Agent

The process begins with fault localization, where the agent takes a crash log as input and identifies both the root cause and the function that needs to be fixed. The crash log must include an ASAN report or, at minimum, a stack trace describing the crash. The fault localization module is implemented using the ReAct approach, allowing the agent to iteratively analyze the code through tool calls designed for source code exploration.

Once the faulty code region is identified, the patch generation module takes

over to produce an actual fix. The patch generation module is also built on the

ReAct framework, enabling the agent to modify source code through tool

interactions and extract the final patch using the git diff command. The

generated patch is then validated through a sequence of steps: project build,

functionality testing, and crash reproduction testing. If the patch fails any

of these validation stages, the agent uses the feedback to re-run the process

and refine the patch until a stable fix is achieved.

ReAct-based Fault Localization

Martian Agent’s fault localization module is inspired by CodeRover-S. Since CodeRover-S demonstrated great performance on real-world bugs (OSS-Fuzz dataset), we developed our fault localization module based on its approach. We developed following code search APIs to help the agent explore the codebase effectively:

- search_symbol(symbol_name, file_or_directory_path): Given a symbol name, it finds a symbol definition in a given path and return the source code of the symbol definition.

- search_string(string, file_or_directory_path): Given a string, it returns the file name and line number(s) where the string appears in the codebase.

- view_file(file_path, offset, limit): Given a file path, it returns the source code of the file from the offset line to the limit line.

With these tools, the ReAct agent can iteratively explore the codebase to identify the root cause of the crash. Similar to the human debugging process, it supports a back-and-forth interaction between understanding the crash log and examining the codebase.

Patch Generation Inspired by Claude Code

Generating a patch is far more complex than simply producing code snippets. Unlike isolated code generation, a valid patch must integrate seamlessly into the existing codebase. This means it must adhere to strict structural and formatting requirements — including correct line offsets, contextual consistency with surrounding code, and compatibility with the project’s build system.

To meet these requirements, we designed the patch generation module to use a search/replace approach, implemented through specialized tool calls and powered by Anthropic claude models. Through extensive experiments, we found that this method consistently produced patches that were both syntactically correct and directly applicable to the source code. Inspired by the Claude Code methodology, we further refined our design by constraining the patch scope to a single function, which reduces context size and allows the model to focus more precisely on the relevant logic. Narrowing the scope could be seemed risky, but in AIxCC competition we observed that lots of the example bugs which shown before the competition were fixed within a single function and thanks to our ensemble system, we could expect other agents to cover multi-function patches.

The patch generation module operates with the following tools:

- view_function(function_name) — Returns the source code of a given function.

- edit_function(function_name, old_string, new_string) — Replaces a specific code segment (old_string) with new content (new_string) within the target function.

- add_import_module(module_name, file_path) — Adds an import statement to the specified file (used only for Java projects).

Dealing with Stack Overflow and Timeout bugs

Beyond general patch-generation strategies, we also developed specialized techniques to handle specific classes of bugs. In the AIxCC competition, certain challenges involved stack overflow and timeout errors. These categories, especially in Java, posed unique difficulties because their Jazzer crash logs often contained little to no information about the actual root cause — unlike conventional Jazzer sanitized logs.

Example of Jazzer timeout log:

==16== ERROR: libFuzzer: timeout after 25 seconds

Stack traces of all JVM threads:

Thread[Reference Handler,10,system]

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.Reference.waitForReferencePendingList(Native Method)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.Reference.processPendingReferences(Reference.java:253)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.Reference$ReferenceHandler.run(Reference.java:215)

Thread[Notification Thread,9,system]

Thread[Finalizer,8,system]

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.Object.wait(Native Method)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.ReferenceQueue.remove(ReferenceQueue.java:155)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.ReferenceQueue.remove(ReferenceQueue.java:176)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.Finalizer$FinalizerThread.run(Finalizer.java:172)

Thread[process reaper,10,system]

at java.base@17.0.2/jdk.internal.misc.Unsafe.park(Native Method)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.util.concurrent.locks.LockSupport.parkNanos(LockSupport.java:252)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.util.concurrent.SynchronousQueue$TransferStack.transfer(SynchronousQueue.java:401)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.util.concurrent.SynchronousQueue.poll(SynchronousQueue.java:903)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor.getTask(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:1061)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor.runWorker(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:1122)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor$Worker.run(ThreadPoolExecutor.java:635)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:833)

Thread[Attach Listener,9,system]

Thread[Common-Cleaner,8,InnocuousThreadGroup]

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.Object.wait(Native Method)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.ref.ReferenceQueue.remove(ReferenceQueue.java:155)

at java.base@17.0.2/jdk.internal.ref.CleanerImpl.run(CleanerImpl.java:140)

at java.base@17.0.2/java.lang.Thread.run(Thread.java:833)

at java.base@17.0.2/jdk.internal.misc.InnocuousThread.run(InnocuousThread.java:162)

Thread[main,5,main]

at app//com.code_intelligence.jazzer.driver.FuzzTargetRunner.dumpAllStackTraces(FuzzTargetRunner.java:534)

Thread[Signal Dispatcher,9,system]

Garbage collector stats:

PS MarkSweep: 0 collections took 0ms

PS Scavenge: 30 collections took 135ms

SUMMARY: libFuzzer: timeout

Example of Jazzer stack overflow log:

== Java Exception: com.code_intelligence.jazzer.api.FuzzerSecurityIssueLow: Stack overflow (use '-Xss921k' to reproduce)

at java.base/java.util.AbstractSet.hashCode(AbstractSet.java:124)

Caused by: java.lang.StackOverflowError

at java.base/java.util.HashMap$KeyIterator.<init>(HashMap.java:1605)

at java.base/java.util.HashMap$KeySet.iterator(HashMap.java:985)

at java.base/java.util.HashSet.iterator(HashSet.java:174)

at java.base/java.util.AbstractSet.hashCode(AbstractSet.java:120)

at java.base/java.util.AbstractSet.hashCode(AbstractSet.java:124)

(... many lines of repeating ...)

at java.base/java.util.AbstractSet.hashCode(AbstractSet.java:124)

... 1 more

DEDUP_TOKEN: e94a000057f77cf1

== libFuzzer crashing input ==

In the case of timeout errors, it was common for every function in the crash log’s stack trace to belong either to the standard Java runtime (JDK) or the Jazzer driver itself, leaving no trace of the project’s code where the issue originated. For stack overflow errors, the situation was similarly problematic: stack traces often displayed a long recursive chain of internal JDK functions, while the most critical portion — the project function that triggered the overflow — was truncated or omitted entirely. In both cases, the patch agent had no reliable entry point for debugging, making it virtually impossible to localize the fault using crash logs alone.

To overcome this limitation, we introduced a runtime stack tracing mechanism. Our system periodically captured the stack trace of the JVM’s main thread every second during the bug reproduction. When a crash finally occurred, the agent used the last recorded stack trace as a more informative snapshot of the program’s execution state. This supplementary trace provided a meaningful starting point for fault localization and enabled the agent to generate plausible patches even for these otherwise opaque bug types.

Conclusion

Martian Agent demonstrates a practical approach to AI-assisted patch generation by combining structured context management, modular tool usage, and iterative reasoning. By separating fault localization and patch generation, and using ReAct-based workflows, the agent can analyze crash reports, explore codebases, and generate patches in a systematic way. Its additional strategies for handling stack overflow and timeout errors show how supplementing standard crash logs with runtime traces can make fault localization more reliable. Overall, Martian Agent provides a useful example of how AI agents can assist in automated debugging and patch generation without overcomplicating the process.