Atlantis-Multilang (UniAFL): LLM-powered & Lauguage-agonistic Automatic Bug Finding

- HyungSeok Han

- Atlantis multilang

- August 20, 2025

Table of Contents

Atlantis-Multilang == UniAFL

Atlantis-Multilang is a fuzzing framework called UniAFL, designed to LLMs for fuzzing across multiple programming languages. Unlike Atlantis-C and Atlantis-Java, it avoids language-specific instrumentation and is intentionally built to be as language-agnostic as possible — both in design and execution. Despite this broad and general approach, UniAFL proved to be highly effective in the AIxCC finals, contributing to 69.2% of all POV (Proof-of-Vulnerability) submissions. This result highlights not only the flexibility of its design but also its strong performance in practice. In this post, we’ll walk you through how we pulled it off, why we made these design choices, and what made UniAFL so effective in practice.

Design of UniAFL

🎯 Language-Agnostic Fuzzing

Challenge Programs in AIxCC were provided in the OSS-Fuzz project format, which supports a variety of programming languages such as C, C++, and Java. Traditional fuzzers, however, often lock themselves into specific languages—or even specific compiler versions—making them less flexible. With UniAFL, we set out to support fuzzing across any OSS-Fuzz–compatible language. While the competition only included C and Java, our design is extensible to Python, Rust, Go, and beyond. No matter the language, the fuzzer should be able to plug in and run.🤖 Boosting Fuzzing Performance with LLMs

A long-standing bottleneck in fuzzing is how effectively inputs are generated and mutated. Existing approaches often improve incrementally, but they struggle with complex targets that demand highly structured inputs. UniAFL leverages LLMs to enhance this process. Instead of relying solely on random mutations, LLMs can infer and generate semantically valid, yet edge-case-driven inputs. This dramatically increases the chances of triggering vulnerabilities. Due to restrictions on LLM usage during AIxCC, we designed UniAFL in a modular way, allowing for multiple levels of LLM involvement—ranging from minimal use to full integration, depending on available resources and rules. Not only for the competition, but also in real-world use, this allows us to pick certain LLM-powered modules depending on the LLM budget.⚡ Optimizing the Fuzzing Pipeline and Development Workflow

Fuzzing shines when run in parallel across many cores, but this also introduces synchronization overhead between fuzzing processes. UniAFL includes optimizations to minimize cross-process overhead, ensuring smooth performance at scale. In addition, supporting multi-language CPs demanded a flexible architecture. We modularized UniAFL so that language-specific components can be added, swapped, or updated with minimal friction. This not only accelerates development but also makes the system easier to maintain and extend.

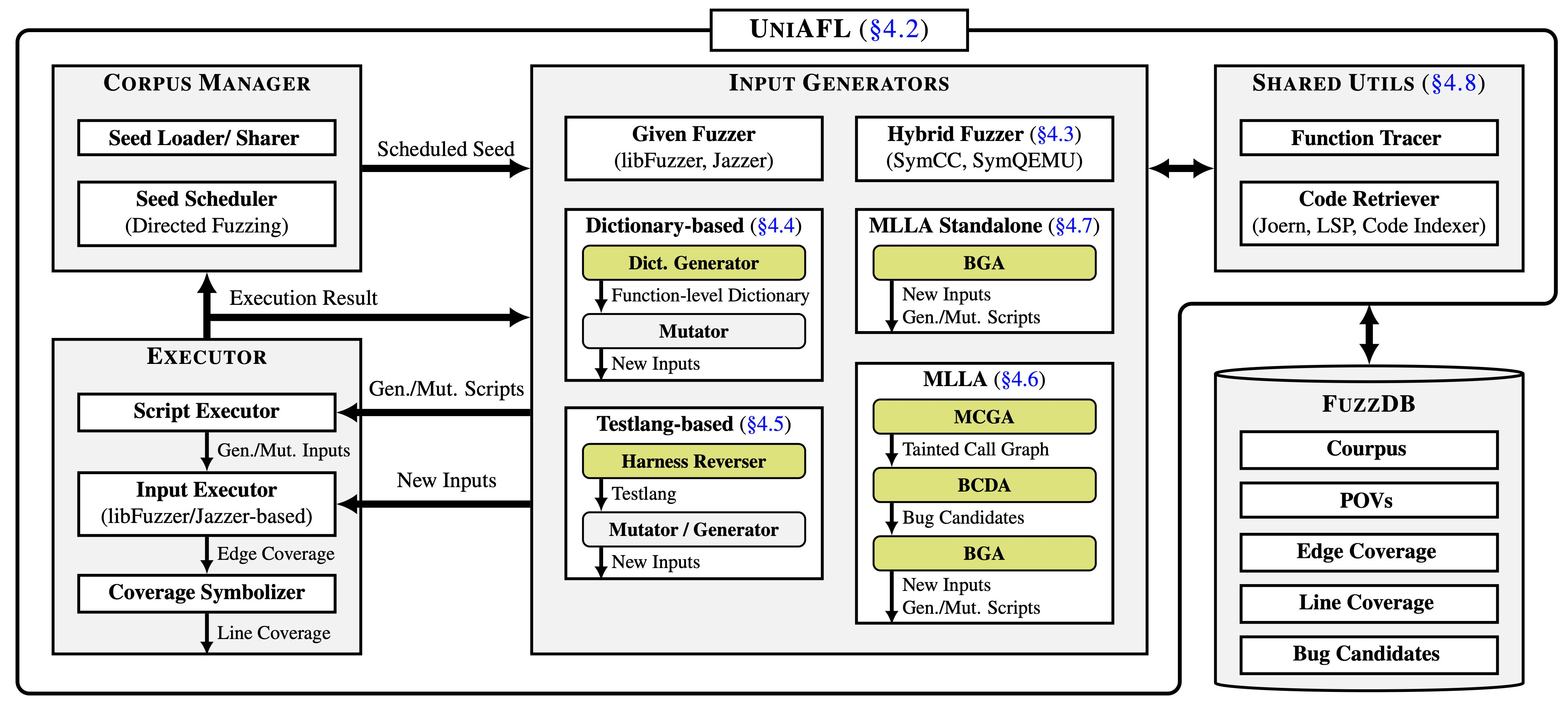

Overview of UniAFL

As shown in the above overview figure, ATLANTIS-Multilang consists of two main components: UniAFL and FuzzDB. UniAFL is the engine that drives fuzzing according to the three design goals we described earlier, while FuzzDB acts as the storage layer, keeping track of everything UniAFL produces – seeds, POVs, coverage data, and bug candidates. Notably, In the figure, the green boxes represent the LLM-powered modules, highlighting the parts of the system where LLM plays a role in enhancing fuzzing effectiveness.

At a high level, UniAFL works much like a traditional fuzzer, but with some unique twists:

- Corpus Manager picks a seed input to start fuzzing, especially directed fuzzing toward bug candidates, which are intermediate results of LLM-powered modules in UniAFL.

- Input Generators then create new inputs either by mutating the seed or generating fresh inputs from scratch. Some of these input generators go a step further: instead of directly producing inputs, they generate Python scripts that generate or mutate inputs, giving us more flexibility in creating structured test cases.

- Script Executor runs those Python scripts, turning them into actual inputs.

- Input Executor feeds those inputs into the target harness and collects execution results along with coverage data.

- Coverage Symbolizer converts raw edge coverage into line coverage — a crucial step, since the LLM-powered modules rely on line-level feedback because LLM cannot understand basic block addresses in raw coverage data.

- Finally, based on execution results and coverage data, Corpus Manager updates the corpus and schedulers to guide directed fuzzing.

This procedure repeats continuously until the fuzzing session ends to explore deeper paths and uncover vulnerabilities.

Inside UniAFL: Six Input Generation Modules

At the heart of UniAFL are its six input generation modules, each designed with a different level of reliance on LLMs. This modular design lets the system balance between traditional fuzzing techniques and AI-powered enhancements.

No LLMs

- Given Fuzzer: the simplest module, running the target harness directly using libFuzzer (for C) and Jazzer (for Java)

- Hybrid Fuzzer: combines fuzzing with concolic execution to explore deeper paths. While the core workflow does not use LLMs, we employed LLMs during development to assist in symbolic function modeling for the concolic executor.

Limited LLM Usage

- Dictionary-Based: uses an LLM to infer dictionaries for a given function, then applies dictionary-based mutations at the function level.

- TestLang-Based: asks the LLM to analyze the target’s input format, express it in TestLang (a specialized input description language), and then generate or mutate inputs accordingly.

- MLLA-Standalone: employs an LLM to write Python scripts that, in turn, generate new inputs.

Full LLM Power

- MLLA: the most LLM-intensive module. It leverages AI to construct tainted call graphs, identify promising bug candidates, and generate targeted inputs or Python scripts that produce mutations specifically aimed at those candidates.

By combining these six modules, UniAFL can flexibly scale its fuzzing strategy from lightweight, language-agnostic fuzzing to deeply AI-driven, bug-targeted exploration. Here are the overall results showing how each input generator contributed in the AIxCC finals and our internal rounds:

+--------------------+--------------------------+------------------------------------+

| Input Generator | Unique POV (AIxCC Final) | Seed Contribution (Internal Round) |

+--------------------+--------------------------+------------------------------------+

| Given Fuzzer | 48 | 69.9% |

| Hybrid Fuzzer | 2 | 0.2% |

| Dictionary-based | 0 | 4.8% |

| Testlang-based | 8 | 42.7% (Separate Seed Pool) |

| MLLA (+Standalone) | 7 | 2.2% |

| Given Seeds, etc | 9 | 22.9% |

+--------------------+--------------------------+------------------------------------+

Looking at the overall results from both the AIxCC finals and our internal rounds, we observed how each input generator contributed. The Given Fuzzer served as the baseline, but on its own it struggled to discover more interesting seeds or POVs. The real breakthroughs came when the other input generators kicked in. They consistently provided meaningful new inputs that helped UniAFL break out of plateaus whenever the given fuzzer got stuck.

What’s Next?

🚀 See upcoming individual posts diving deeper into each input generator and the UniAFL infrastructure!

🌐 Check UniAFL Source Code!

🧠 Explore MLLA: The Multi-Language LLM Agent System