Sinkpoint-focused Directed Fuzzing

- Fabian Fleischer

- Atlantis java

- August 19, 2025

Table of Contents

Traditional coverage-based fuzzers excel at code exploration.

When testing Java code, however, most vulnerabilities require the invocation of a certain Java API, such as creating an SQL statement (java.sql.Statement) for an SQL injection bug.

Thus, we target such security-critical APIs with our modified, directed Jazzer to reach and exploit critical code locations faster.

This blog post gives an overview over our directed fuzzing setup for Java challenge problems.

Calculating a distance metric for directed fuzzing requires static analysis to identify critical code locations (aka sinkpoints) and compute distances. This static analysis happens mostly offline, independent of the modified Jazzer, to reduce the computational overhead in the fuzzer. However, we still compute the CFG (and, thus, basic block-level distances) in Jazzer to maintain a precise distance metric and allow the update of seed distances during fuzzing.

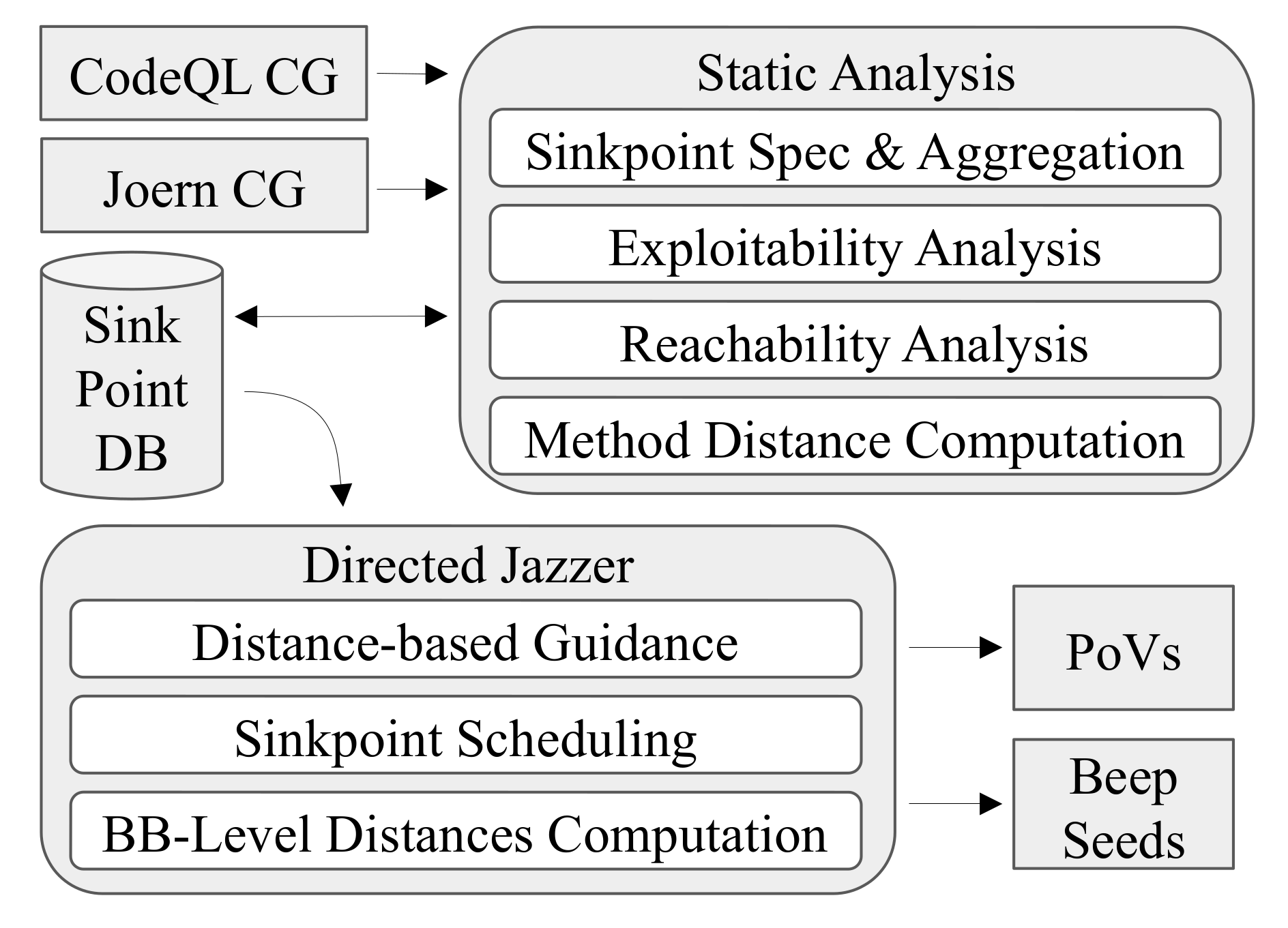

Figure 1: Overview of sinkpoint-focused directed fuzzing architecture.

Splitting up the calculation of the iCFG is also observable in the overview of our directed fuzzing architecture (Figure 1). In an ideal world, we would perform the entire static analysis outside of Jazzer to improve fuzzing performance; particularly, we need to keep the startup overhead low since Jazzer may restart frequently on certain targets, for example, if they consume large amounts of memory. However, calculating precise basic block-level distances ahead of time proves challenging under the given competition constraints.

Basic block-level distances. There mainly exist two approaches to pre-compute basic block-level distances: 1) Assigning distances to coverage IDs and 2) assigning distances to basic blocks/instructions.

Coverage ID Assignment: Jazzer assigns coverage IDs dynamically during class loading, making them non-deterministic. The assignment order depends on when classes get loaded during execution, which varies based on fuzzing inputs and execution paths. While Jazzer can pre-assign IDs by rewriting JAR files, we avoid this approach for competition stability reasons.

Bytecode Instruction Matching: Even if we pre-compute the CFG, matching pre-computed distances to post-instrumentation basic blocks proves challenging. Jazzer’s instrumentation modifies bytecode in ways that affect instruction offsets:

- The runtime constant pool grows larger due to added coverage instrumentation

- Original instructions change from

ldctoldc_worldc2_wwhen constant pool indices exceed 8-bit limits - These changes cascade through the bytecode, shifting offsets of subsequent instructions

- Basic block boundaries can shift unpredictably due to these instruction size changes

While heuristic matching approaches exist (e.g., matching by instruction patterns or control flow signatures), the competition environment demands high reliability. False or missing matches could misdirect the fuzzer toward incorrect targets, potentially worse than no guidance at all.

Design Decision: Given these constraints, we split the interprocedural CFG computation: call graph analysis happens offline during static analysis, while control flow graph construction occurs online within Jazzer. This design trades some performance for precision and reliability, ensuring accurate distance calculations even as bytecode gets modified during instrumentation.

Static Analysis

Our static analysis pipeline detects sinkpoints, checks reachability and exploitability, and calculates sinkpoint distances in the call graph. Recognizing that no single analysis tool provides complete call graph coverage, we merge the call graphs from multiple frameworks including CodeQL, Soot, and Joern as well as from dynamic execution traces. This multi-tool approach handles Java’s complex object-oriented features where interface calls and reflective invocations often confound individual analyzers.

Sinkpoint Detection. While Jazzer has a list of sinkpoint APIs which it sanitizes, we identified additional APIs that are likely to trigger vulnerabilities. Our CodeQL component establishes a framework for specifying security-sensitive APIs that extend beyond Jazzer’s built-in sanitizers. Rather than exhaustively analyzing every library dependency, our approach extends the sink API list while focusing analysis only on challenge problem code instead of all dependencies.

# Example sink definition for java.net.URL

- model: # URL(String spec)

package: "java.net"

type: "URL"

subtypes: false

name: "URL"

signature: "(String)"

ext: ""

input: "Argument[0]"

kind: "sink-ServerSideRequestForgery"

provenance: "manual"

metadata:

description: "SSRF by URL"

We added sinkpoints for additional vulnerability classes including java.math.BigDecimal (DoS), networking APIs (SSRF), validation frameworks (expression injection), and XML/SVG parsers.

This approach reduces analysis time from hours to minutes by focusing only on challenge problem code rather than exhaustively analyzing all dependencies, leaving maximum time for directed fuzzing.

Reachability Analysis. We perform per-harness reachability analysis to ensure that sinkpoints are only scheduled in the directed fuzzer, if they are accessible from the harness entry point, eliminating unreachable targets that would deflect the fuzzer’s attention.

Exploitability Analysis. Beyond identification, we assess whether sinkpoints are practically exploitable by analyzing data flow patterns. When we find strong evidence that a sinkpoint is not exploitable (hardcoded arguments, untainted inputs), we filter it out. This transforms large lists of potential targets (hundreds to thousands) into manageable sets of high-value sinkpoints (typically under 100).

Method-Level Distance Computation. The static analysis phase pre-computes method-level distances from harness entry points to all reachable sinkpoints using the merged call graph. These cached distances are combined with the runtime basic block-level calculations, to determine the distance of a given fuzzing input.

Directed Jazzer

Our enhanced Jazzer transforms static analysis insights into dynamic fuzzing guidance through two main components:

Distance Metric Calculation. During fuzzing execution, we compute basic block-level distances in real-time using Soot’s control flow graph analysis. The system combines pre-computed method-level distances with runtime basic block distances to guide input mutation toward sinkpoints. The distance metric itself uses an off-the-shelf formula: We calculate the average distance of each basic block given the trace of a seed, with the basic block distance being the sum of the method distance and the intra-CFG distance to the next level in the CG.

Sinkpoint Scheduling. Our scheduler schedules up to 15 concurrent sinkpoints using prioritized round-robin scheduling. The system uses two separate queues to implement prioritization: one queue contains all active sinkpoints, while a second queue contains only high-priority sinkpoints from SARIF reports or diff mode. The round-robin scheduler consideres both queues, effectively scheduling SARIF and diff-related sinkpoints twice as frequently as regular sinkpoints. This dual-queue approach ensures that competition-relevant sinkpoints receive appropriate focus while maintaining systematic coverage and a scheduling guarantee for all sinkpoints.

Evaluation

We evaluated our directed fuzzing approach on our own benchmark suite. As expected, directed fuzzing improves performance on benchmarks with certain characteristics, where sinkpoints are difficult to reach, such as ActiveMQVar. For targets where traditional fuzzing immediately reaches sinkpoints, directed fuzzing provides no additional benefit. ActiveMQVar represents a challenging case with a wide call graph and multiple code paths, making it difficult for coverage-based fuzzing to efficiently reach all specific sinkpoints.

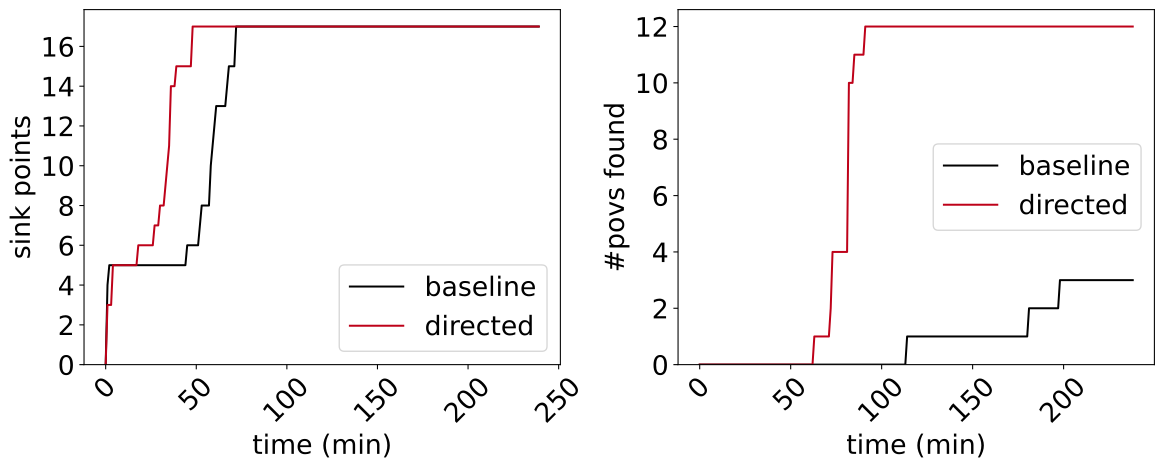

Figure 2: Directed fuzzing evaluation result on our ActiveMQVar benchmark.

Results: Our directed approach achieved faster sinkpoint discovery compared to standard Jazzer after initial setup time (Figure 2). Within the 4-hour evaluation timeframe typical of the competition scenario, directed fuzzing successfully identified all 12 ground-truth vulnerabilities. The system detected additional sinkpoints beyond the 12 true positives; however, the small number of false positives did not significantly impact overall performance.

Our investigation on the benchmark suite found that directed fuzzing provides substantial benefits in scenarios with wide call graphs where traditional approaches struggle to make progress toward specific targets. The initial overhead of static analysis and setup is quickly amortized by more efficient sinkpoint reaching, leading to faster overall vulnerability discovery.

Conclusion

With our directed fuzzing framework, we ensure that the fuzzer reaches critical code locations faster than traditional approaches. By combining static analysis with runtime distance computation, we create a system that efficiently navigates toward sinkpoints while avoiding the computational overhead of full dynamic analysis. The approach proves particularly valuable in the time-constrained competition scenario where reaching security-critical code quickly is essential for effective vulnerability discovery.

This precision-guided approach represents a significant evolution beyond coverage-based fuzzing, focusing computational resources on the code locations that matter most for security testing.

References

- Directed Jazzer modifications

- Static analysis components based on CodeQL and Soot

This post is part of our series on Atlantis-Java components. We already explored our LibAFL-based Jazzer integration for enhanced mutation diversity. Check back later for more.