Our GraalVM Executor: How We Achieved Compatibility, Scale, and Speed

- Dongju Kim, Kyungjoon Ko, Yeongjin Jang

- Atlantis java

- September 29, 2025

Table of Contents

In the AIxCC competition, while fully committing to the challenge of leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs), we also integrated traditional techniques to create a more robust bug-finding system with fewer blind spots.

The competition provided a baseline fuzzer (Jazzer for Java projects), but coverage-guided fuzzing in general often struggles with the complex validation logic that guards deep code paths. To address this, concolic execution is a well-known solution for exploring these paths by solving their input conditions. Our main challenge, therefore, was how to effectively leverage this powerful technique for the competition’s bug-finding goals.

Why a New Java Concolic Engine?

This proved more challenging than anticipated. We found that while many existing Java concolic engines were powerful in theory, applying them to the competition’s demands revealed a fundamentally unstable foundation. These issues made them unsuitable for our purposes:

- Outdated Java Support: Many existing tools only supported older Java versions (like 8 or 11), making them incompatible with the modern applications we needed to analyze.

- Foundational Instability: The primary issue was a deep-seated instability stemming from two sources.

- At a low level, their core bytecode instrumentation method often clashed with essential Java features like class initialization (

<clinit>) or lambda expressions, causing the tool to crash on perfectly valid code. - At a high level, they were fragile when faced with real-world applications that use native methods or complex external libraries, which require time-consuming and error-prone manual modeling. This combined instability meant the analysis could fail unpredictably, making the tools fundamentally unreliable—akin to building castles on sand.

- At a low level, their core bytecode instrumentation method often clashed with essential Java features like class initialization (

- Significant Performance Overhead: Concolic execution is inherently resource-intensive—a fundamental challenge for any implementation. A key goal for us was to mitigate this overhead as much as possible for the competition’s tight time constraints.

These obstacles motivated us to build a new concolic executor from the ground up, one aimed at being robust, compatible, and performant enough for the demands of the competition.

Our Approach: Interpreter-Based Symbolic Emulation

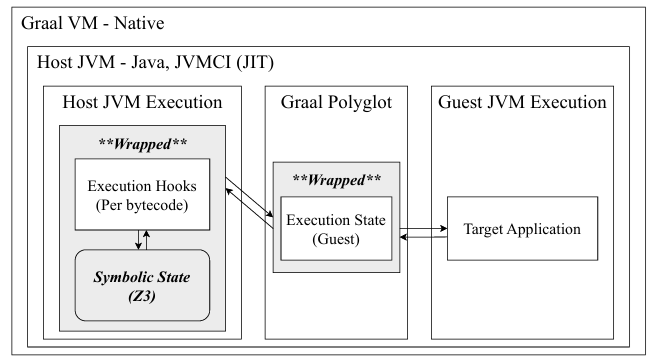

Fig.1 High-level overview of our Concolic Executor

To overcome the critical issues of bytecode instrumentation, we built our engine on GraalVM Espresso, a high-performance, JIT-compiled bytecode interpreter. This interpreter-level approach gave us several key advantages:

- Compatibility Without Instrumentation: By operating at the bytecode level, we can hook into every execution step without modifying the target program’s code, ensuring compatibility with the latest Java versions.

- State Isolation: Our symbolic analysis runs in a completely isolated context. The target application is entirely unaware of the symbolic state tracking, which prevents the contamination issues that plague static instrumentation methods.

- JIT-Accelerated Performance: Symbolic execution adds overhead. Our engine leverages GraalVM’s Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler to mitigate this. After a code path is executed once, it’s JIT-compiled, making subsequent runs—for both the program and our symbolic emulation—execute at near-native speed.

What We Focused On

To be effective alongside fuzzers like Jazzer, our executor needed to excel at two things: reaching sinks and triggering bugs. To achieve this, our engine collects path constraints during execution and uses the Z3 solver to generate new inputs that either guide the fuzzer toward unexplored code (exploration) or satisfy the precise conditions needed to trigger a vulnerability (exploitation).

For Exploration: Reaching the Unreachable

In mature fuzzing campaigns, fuzzers can get “stuck” repeatedly exploring the same regions of code without making new discoveries. Our concolic executor addresses this by recording the path constraints that lead to these stuck points, negating them, and using the Z3 solver to generate new inputs that bypass the roadblock.

This new input then guides the fuzzer to explore previously unreachable code blocks, significantly improving coverage even on corpora from long-running fuzz campaigns. By systematically navigating past these difficult barriers, we increase our chances of reaching new, security-sensitive sinks.

For Exploitation: Triggering Vulnerabilities

Sometimes a fuzzer successfully reaches a sensitive API (a sink) but fails to provide the specific input needed to trigger the vulnerability. This is where our executor shines as an “exploit assistant”.

Example: OutOfMemoryError

In an Apache Commons Compress challenge,

a vulnerability could be triggered by allocating an enormous array, causing an OutOfMemoryError.

The allocation size was determined by complex calculations based on the input.

protected void initializeTables(final int maxCodeSize) {

...

if (1 << maxCodeSize < 256 || getCodeSize() > maxCodeSize) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("maxCodeSize " + maxCodeSize + " is out of bounds.");

}

final int maxTableSize = 1 << maxCodeSize;

prefixes = new int[maxTableSize]; // Out-Of-Memory

characters = new byte[maxTableSize]; // Out-Of-Memory

outputStack = new byte[maxTableSize]; // Out-Of-Memory

outputStackLocation = maxTableSize; // Out-Of-Memory

Our engine identified the array allocation bytecode (NEWARRAY) and used Z3’s Optimize feature

to find an input that both satisfied all path conditions and maximized the allocation size,

demonstrating the ability to reliably trigger the OOM error.

Example: OS Command Injection

Since our executor works alongside Jazzer,

it can leverage Jazzer’s bug detectors, which often look for specific sentinel values.

For command injection, Jazzer’s detector reports a finding when the executable name is equal to "jazze".

final DataInput inData = new DataInputStream(in); // Input

final int method = inData.readUnsignedByte();

if (method != Deflater.DEFLATED) { // Validation 1

throw new IOException("Unsupported compression method " + method + " in the .gz header");

}

final int flg = inData.readUnsignedByte();

if ((flg & GzipUtils.FRESERVED) != 0) { // Validation 2

throw new IOException("Reserved flags are set in the .gz header.");

}

long modTime = ByteUtils.fromLittleEndian(inData, 4);

...

String fname = null;

if ((flg & GzipUtils.FNAME) != 0) { // Validation 3

fname = new String(readToNull(inData), parameters.getFileNameCharset());

parameters.setFileName(fname);

}

if (modTime == 1731695077L && fname != null) { // Validation 4

new ProcessBuilder(fname).start(); // Sink

}

Fuzzers often struggle to generate this exact string when it’s constructed

after multiple transformations or guarded by the validation checks shown above.

Our solution was to add a simple constraint once the ProcessBuilder sink was reached:

that the executable name must equal "jazze".

The Z3 solver could then handle the complexity of satisfying this goal

while also passing all other path conditions.

Thus, by combining the broad reach of fuzzing with the deep, targeted analysis of our solver-powered concolic executor, Atlantis-Java strengthened its ability to uncover vulnerabilities that were deeper and more complex than either technique could find alone.